Sir John Fortescue

15th Century Chief Justice of the King's Bench, MP, and author of 'De Laudibus Legum Angliae' and ‘On the Governance of England’

Even in the 15th century, there were complaints that there were too many lawyers. It was even discussed in Parliament, and Bills were passed to limit their number. Yet one of them became the first man to write in English about the constitution, and what he wrote resonates to this day. Indeed, his arguments could be applied to the reasons for, and even the necessity of, Brexit.

The date of Sir John Fortescue’s birth is uncertain. He became a Serjeant-at-Law in 1429 or 1430, and wrote that no one could reach this eminence who had not studied the law for sixteen years. From that, it can be deduced that he was born in the middle of the 1390s. The date of his death is equally unknown, but he is buried in Ebrington in Gloucestershire, where local tradition maintained that he lived to be ninety. The last record of his life was in 1476, so he certainly achieved a great age.

Fortescue was a lawyer and a judge, and claimed to be Henry VI’s Chancellor, as well as being the Chief Justice of the King's Bench. He was a loyal Lancastrian during the Wars of the Roses. Following the disastrous defeat of the Lancastrian army at Towton in 1461, he went into exile in Scotland. In 1463 he went with Queen Margaret (Henry VI’s consort) and the Prince of Wales to Flanders, where he lived in very reduced circumstances.

He returned to England, landing in Weymouth, in 1471, but on that very day Henry VI had been defeated and the Lancastrian cause was finished. For his pains, he was attainted by the Yorkists. To be attainted is a process technically still open to Parliament, whereby someone is declared to be a malefactor and has his land, and possibly his life, taken away. He was fortunate to survive, as he was arrested and held prisoner after the Battle of Tewkesbury in May 1471. However, he was pardoned by Edward IV that October, and was made one of the King’s Councell. In order for his attainder to be reversed, he had to write in favour of the King’s right to the throne, which he did, and was fully restored to his estates in 1475.

Fortescue’s legal reputation was high, both in his lifetime and subsequently. In an age of sometimes corrupt judges, he was thought of as honest and as a fair Chief Justice. Interestingly, he ruled, as a precursor to the Bill of Rights 200 years later, that he could not interfere on a matter that related to ‘the privilege of this High Court of Parliament’. He married well and by special good fortune, to a Somerset lady, Isabella or Elizabeth, the daughter and heiress of John Jamyss of Norton St Philip, near Bath. This brought him land, and then children, one son and two daughters, and the Earldom of Fortescue descends from him and still exists today.

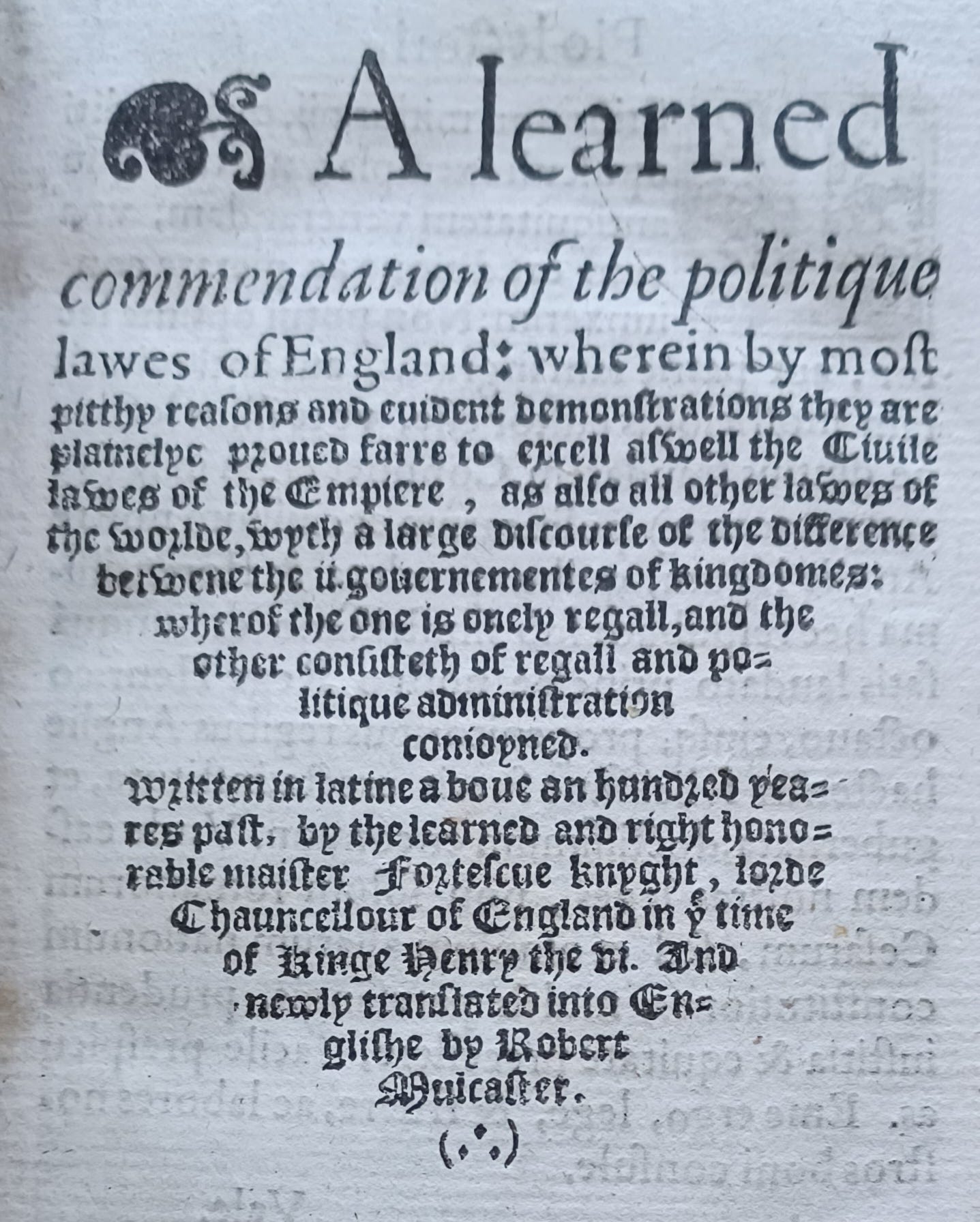

However, his life, although not without interest, is not of much importance, and he would have passed into obscurity like most medieval figures, were it not for his writings. In his lifetime, printing was in its infancy, and his first work was not published until 15371, well after his death. ‘De Laudibus Legum Angliae’ is a book that encourages the heir to the Throne to understand the laws of England, so that he could become a good King. It was a book used by lawyers for more than a century after his death, and was much admired by Sir Edward Coke, the 17th century jurist, whose rulings still have a profound effect on the way we are governed today.

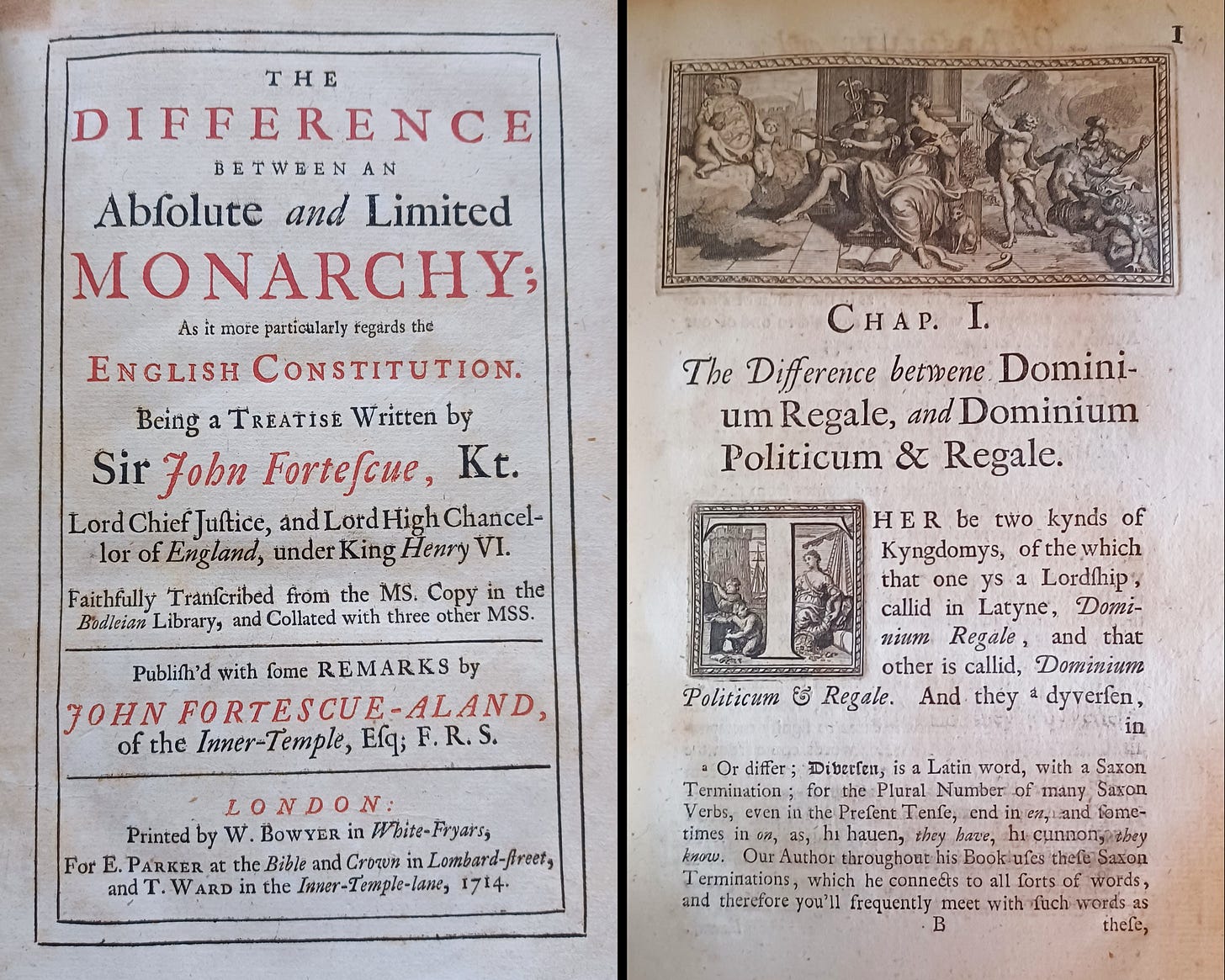

Nonetheless, Fortescue’s greatest contribution was not published until 17142. ‘On the Governance of England’ is the first English language explanation of the constitution and its effect on our prosperity. He set out how it underpins the nation, in comparison with France. In this country the King is under the law, whilst in France the King is the law. This bottom-up, as opposed to top-down, approach is fundamental to how the two nations have developed and, incidentally, is one of the reasons why Brexit had to happen.

That it was published in 1714 is a fascinating historical footnote. After the Wars of the Roses, a number of the Tudors and Stuart Monarchs tried to impose a totalitarian, absolutist monarchy, but failed. However, by the beginning of the 18th century the country was tentatively developing a more democratic form. Or, at least, the practice of parliament was coming closer to the theory.

Fortescue’s argument was that there are two kinds of kingdom, a Dominum Regale and a Dominum Politicum et Regale. In the first, the King may make laws and tax people as he pleases, but in the second the people who are ruled must assent to such laws and taxes. Fortescue used the authority of no less a figure than St. Thomas Aquinas to argue that the second system is much less likely to fall into tyranny and, therefore, will provide better government.

It is worth remembering that in Sir John’s time, and for many centuries afterwards, people did not debate how democratic a government was, but what would lead to the best form of government. The concern was always about tyranny and how that could be avoided. Hence the arguments in favour of a benign dictator, with the risk always being that the benignity of the dictator could not be guaranteed in future generations or, indeed, maintained by a single person.

In France, because the consent of the people was not sought, the King taxed at will, but only taxed those who could not refuse. Thus the charges fell on the poor, as the nobles were excluded from taxation for fear that they would rebel and try to oust the King. This meant that the peasants ‘live in the most extreme poverty and misery, and yet dwell in the most fertile realm of the world’.

In England, on the other hand, ‘Blessed be God, this land is ruled under a better law’. The reason for French poverty on such fertile soil is that if a French peasant invested in his land and improved it, this more profitable land could then be arbitrarily confiscated by the King for his benefit. This meant that there was no incentive for the peasants to invest and so no improvements were made. In England, the peasant not only kept the fruits of his labour, but had the opportunity to move up the social scale by working hard. This provided the necessary incentive for them to exceed the level of effort needed for mere subsistence existence, which helped make the country richer.

This has further consequences, because Fortescue saw the need for the commons (by this meaning not the House of Commons, but the bulk of the people) to be rich so that, when necessary, they could form a citizen’s army to protect the kingdom. He noted that France was very dependent on mercenaries, which it was harder for England to use because it is an island.

How does this translate into modern times? It relates directly to the status of society, and the common law versus the civil code. Is the state (rather than the King) the total authority, or is the state still subject to the law?

In the European Union, the state is the law. When we were members, it could overrule all the parliaments and elected governments. For example, the European Court could rule on its own pension rights; it could not be challenged.

In this country all laws, now that we have left, are subject to the will of a democratically elected Parliament which is answerable to the people.

In the EU, law is based on the civil code, where precedent has no formal role, and it always goes back to the text on which the law is based, which may be purposefully interpreted. That is to say, the judges’ interpretation of the intention of the law may be taken into account, rather than its strict formulation.

In contrast, the British Courts have to follow the text that is passed into law by Parliament, and are not allowed to consider what Parliament may have intended, except in very particular circumstances when the law is unclear. Indeed, our courts are prohibited, as Fortescue noted, from considering what is said in Parliament during the passage of a Bill. Here, the common law is entirely precedent based, unless Parliament has decided to change or clarify it. This has the effect of making everything in the UK allowable, unless specifically prohibited; while in the EU generally only things that are specifically allowed are lawful.

EU law developed from the French system. The King was the law, the state now is the law. Thanks in part to Napoleon spreading French law across it, the continent of Europe has long operated on this basis, but it inevitably clashed with the British system. During our membership of the EU we repeatedly found that the absolutism of the state contradicted our doctrine of Parliamentary sovereignty, as well as the ability of citizens to seek redress of grievance.

In a book written about 550 years ago, and published over 300 years ago, Sir John Fortescue made it clear what the difference was. If asked, I am sure that he was have predicted that trying to replace a Dominum Politicum et Regale with a Dominum Regale was doomed to fail.

1 The first illustration is from the second edition, published in 1573.

2 The second illustration is from this edition.

Sources:

The Governance of England, a revised text by Charles Plummer, 1885

The Dictionary of National Biography

Note on quotations: I have modernised the English in the quotations taken from Sir John Fortescue’s works. I thought, for example, that “Blessyd be God, this lande is rulid vndir a bettir lawe” may be intellectually pure, but not particularly easy to read.

If you have enjoyed this article, then please do share it with your friends.

Your comments on this article would be most welcome. Please click the button to join the conversation. Thank you.

Thanks be that the EU and its dubious accounting is no longer leaching our taxes. The Fraud record is mind boggling. Check it out for yourselves.

A fascinating and interesting article